by Todd Kliman

If you order a crab cake at a local restaurant, you might assume you’re getting a product from the Eastern Shore. Chances are, it’s from the Far Eastern Shore.

All journeys to enlightenment begin somewhere. Mine began in a grocery store.

I was standing in my supermarket one afternoon about a year ago, considering a black-labeled tin of Phillips lump crabmeat, when my eye fell on this eye-straining, agate-sized disclosure: “Serving the finest seafood in the mid-Atlantic region from the tropical waters of S.E. Asia.”

So much to unravel in a single phrase!

I gave the can a turn, and there was Shirley Phillips’ own “Maryland-style” crab recipe, an authenticating stamp intended to convey to consumers like myself a sense of continuity and tradition.

Phillips was a name I knew well; everyone who grew up in the area knows Phillips. The local chain restaurants were and are friendly, family-style places specializing in seafood, where you can buy T-shirts and crab seasoning on your way out. Legions of college students have supported their way through summers in Ocean City at Phillips. But “S.E. Asia”?

Several phone calls after the grocery-store revelation, I’m sitting in the airy loft office of Honey Konicoff, the vice president of marketing for the Baltimore-based Phillips Foods, eager to begin the unraveling. I find myself trying to reconcile the Phillips I remember with the slick outfit I’m being presented in an elaborate, timed-to-the-minute tour.

The story of Phillips is the stuff of legend, one of those reassuringly American sagas of hard-earned upward mobility. It began with A.E. Phillips, who established a crab-processing plant on the Chesapeake Bay’s Hooper’s Island in 1916. Son Brice Phillips and his wife—the Shirley whose recipe adorns the can—opened Phillips Crab House in Ocean City, Md., in 1956, a white clapboard structure with four seats and a screened-in porch. Over the next four decades, as the beloved original begat an outlet in Baltimore’s Harborplace, another on the waterfront in Washington, and two more in Ocean City, the Phillips name became as emblematic and trusted in the region as Brennan’s was in New Orleans. Through it all, the business remained a family affair. In the ’80s, Brice and Shirley stepped aside and their son Steve assumed the job of running the company, a position he retains to this day.

So the corporate atmosphere at the retrofitted Coke plant that serves as the Phillips world headquarters—“A Mr. Kliman is here to see you”—has come as a surprise.

As has the fact that throughout the vast, light-filled building, employees continually refer to “the brand” and “viable avenues for growth,” reminding me at every turn that the lovably homespun Phillips Seafood Restaurants has ceded the floor to the proactive, market-conquering Phillips Foods.

The upstairs employees, that is. Downstairs is the “mixing room,” where an army of women in hairnets and gloves, moving with rote precision in the refrigerated gloom, pack the steamed and picked crab shipped in from Southeast Asia into cans, or stamp it into uniform patties that will be flash-frozen, or stir it into the various soup bases that sit in 500-gallon tanks. By the close of business, these workers will have produced as many as 120,000 crab cakes, to be sold to some 18,000 retail outlets.

Konicoff regards me coolly from across a desk covered with proposed packaging designs for Phillips’ new frozen dinners as I take in the company’s agency-produced promotional video. The second it’s over, the VP offers up a flurry of facts. There is a connection, she insists, between the crab from the Chesapeake Bay and the crab from Southeast Asia that the company now uses. The Atlantic blue crab—Callinectes sapidus—“is a cousin” to the Southeast Asian swimming crab—Portunus pelagicus.

But aren’t all crabs “cousins”?

I’ve just seen the video. The two crabs don’t look anything alike. The Asian crabs are not blue and gray and smooth but white and spiny and spotted, with thicker claws and a noticeably fuller body.

And the two crabs don’t taste alike, either. The flavor of the meat from the Asian swimming crab doesn’t begin to approach the distinctiveness of the meat from the Chesapeake Bay’s blue crab, lacking the latter’s sweet, musky succulence.

Konicoff returns serve a week later by shipping me a couple of cans of Phillips lump crab, with instructions to mix the meat with mayo, Worcestershire sauce, and mustard—“the way most people do who use the product.”

I try to keep an open mind, but the crab cakes my wife and I eat that night are pale approximations of what we know to be Maryland crab cakes; they only make us pine for the real thing. What I regard as a sort of signal deficiency—the strikingly mild taste of Phillips crab—which results, Konicoff explains, from “pasteurization”—Konicoff regards as delicacy, subtlety.

We can argue the point all day, and for a while there during our follow-up call, it seems as if we will. But that is a matter of taste. This is a matter of fact: Phillips may be offering “Maryland-style” crabmeat recipes, but it is no longer selling Maryland crabmeat.

Going offshore is nothing new. Many large, dominion-minded American companies have aggressively sought to exploit overseas suppliers in recent decades. But crab?

Crab is not like cell phones or TVs or computers. It’s not an item of mass production.

Or wasn’t. Just as Phillips wasn’t anything more than a glorified mom-and-pop.

According to A.C. Nielsen, Phillips’ is now the No. 1–selling crabmeat in the country, providing an estimated 70 percent of the crabmeat sold in the United States to wholesale restaurant suppliers and grocery stores. Phillips Foods, a company that eight years ago recorded sales of $10 million a year, is expected to reach $500 million a year by the end of the decade.

Those numbers only begin to hint at Phillips’ profound impact. Its reach is long and wide. Foreign and domestic. Wholesale and retail. Big-name restaurants and neighborhood joints. In this area, restaurants as different as the middlebrow Cheesecake Factory and the jackets-only, expense-account Palm favor Phillips’ imported product.

Which raises the question: How can you know anymore if you’re getting local crabmeat when you go out to a restaurant? The answer: You can’t. Your chances of getting regional crabmeat? Depends on where you’re eating out. These days, all you can be sure of is that it’s still going to cost you.

That’s not to say, however, that top dollar is any guarantee that your crab cake has been formed from local blue crab. The market has been so radically transformed by Phillips’ outsourcing that buying imported meat has lost much of its stigma among restaurateurs. Crabmeat from Venezuela, from Mexico, from Ecuador—all of it picked from crabs that belong to a species of Callinectes—now vies with crabmeat from Asia for the affections of bargain-hunting chefs. Some restaurants serve imported crabmeat blended with a small amount of local crabmeat; some go a step further, serving imported meat mixed with a flavoring derived from blue-crab innards purchased from local suppliers.

According to Todd Schiller, the executive sous chef at Kinkead’s, which is renowned for its seafood, sometimes the restaurant uses Maryland crab, sometimes it uses imported crab, and sometimes it uses both. It just depends. At the moment, Venezuelan jumbo lump is selling, wholesale, for $15 a pound, so the restaurant is using that. Compare that price with $18 a pound for jumbo lump from a supplier of local crab called Baxter Softshell Crab, in St. Michael’s, Md. Three dollars a pound may not sound like that much money, but consider that the restaurant goes through 40 pounds of jumbo lump crab a day.

Louis Foehrkolb, a crab processor in Jessup whose eponymous brand is a favorite of a number of local restaurants, including Clyde’s, Ceiba, TenPenh, DC Coast, and Kinkead’s, switched from providing exclusively local product a few years ago. Foehrkolb testifies to Phillips’ enormous influence even as he tries to deny it. “You don’t take their lead,” he says. “You take what you customers are asking for or demanding.”

And what are his customers demanding? Lower and lower prices. And how is Foehrkolb supposed to satisfy that growing need? By going offshore.

Foehrkolb defends the practice, first by saying that the technology overseas has improved, then by saying that the provenance of the crab doesn’t matter to the people he sells to—“It’s like anything else: As long as you don’t get a bad pound of crabmeat, you don’t care where it’s from”—and finally by saying that his peers are gaining on him.

“If you’re not going to supply it,” he says, “someone else will do it. It’s just a fact. Sometimes I feel sorry for the producers in this country. But you know, it’s a fact of life now.…You either get in the game or you’re out of business.”

New England has its clams, Louisiana its shrimp, Texas its beef barbecue. And in the mid-Atlantic, we have our crab. More than any single foodstuff, the Chesapeake Bay blue crab has come to define this region.

Those of us who grew up in the metropolitan area are accustomed to the tiresome culinary complaints of the transients. So accustomed that most of the time we don’t even bother coming up with a proper refutation. Fine, we lack good pizza. Fine, the bagels are subpar. Fine, there’s no distinctive sandwich to call our own—no cheesesteak, no hoagie, no Chicago hot dog. (The half-smoke? Please.)

But about Maryland blue crab, we locals have always been proprietary. It’s one of the few things in this fractured metropolis that bind us together, give us pride in ourselves. Bring up the word “Dungeness” around these parts and you’re asking for a fight. I once saw a guy in a bar being shouted down and invited to get the hell out of town, just for suggesting that Gulf crab tastes pretty good.

Crab has always meant blue crab around here. Those who know it and love it will have already experienced the familiar chain reaction of sensual association: the supple, indefinable texture that manages to convey, in a single bite, both resiliency and give, richness and delicacy; the almost funky sweetness that simultaneously conjures up watery depths and well-appointed dining rooms; the creamy, mustardy residue that lingers on the palate long after the meat has been devoured. Only the blue crab, alone among the multiple varieties of these side-scuttling sea dwellers, possesses this particular profile.

But that’s not what makes it so special.

What makes it so special is what has, traditionally, made any other foodstuff special, from caviar to lobster to truffles: its relative lack of availability.

In Feeding a Yen, Calvin Trillin writes of a category of food “that can be eaten only in its place of origin.” The blue crab’s seasonality and its regionality—you can find it only in this particular region, only at this particular time of the year—is what makes it it. If you take the regionality and the seasonality from the crab, you are ultimately taking the crab from the crab, too.

As profound as the American food revolution of the past 25 years has been, there have been more powerful influences at work on our society during that time: consolidation, corporatization, globalization. As fast food and convenience food have supplanted family dining, regionality and seasonality—once the privilege of all classes and the glue that held communities together—have become quaint, almost antiquated notions. Globalization has made it possible to get anything you want, when you want it, without regard to nature’s dictates.

Of course you’re going to rejoice at the fact you can lay your hands on a big, fat Omaha Steak in Tuscaloosa, Ala. And well you should. Some foods lose little in being turned over to mass production.

But some foods lose a lot. That tomato in February, harvested in a hothouse in Chino, Calif.? Beautiful, pinkish-red mush. Those wonderfully verdant asparagus from Chile in December? The weeds in my yard have more flavor.

Crabmeat is a lot closer to produce than it is to steak. Overhandling, a common occurrence with all mass-market goods, destroys its texture. It has a limited shelf life, and it can’t be frozen without damage to both flavor and texture. In short, crabmeat, being so delicate, was not meant for the abuse that comes of being canned and shipped halfway around the world.

Not that Phillips and others don’t try their best to correct for these imperfections. Thanks to trace amounts of a chemical additive called SAPP (sodium acid pyrophosphate), the meat is well-preserved, and prying open the black Phillips can gives you a glimpse of big, whole lumps of alabaster meat—far whiter and smoother-looking than local crabmeat. If you were to eat it in Asia, directly from the source—who knows, it might even taste good.

The story of the repositioning of Phillips from a local fixture to a business behemoth with a brand-name retail presence is the story of luck and foresight. And opportunism.

By the late ’80s, the crab supply that “drove the business”—two-thirds of the menu at Phillips restaurants was crab—was drying up, the result of overfishing, development, and efforts to resuscitate a dwindling rockfish population in the Bay. Steve Phillips, fearing what would become of his family’s business without a dependable, year-round supply of crab, was panicking. He flew to Florida, Texas, and Louisiana in search of a supplier but came up empty.

Then he came across an article about the existence of a crab in Asia whose “flavor profile” was said to be similar to the Atlantic blue crab’s. He thought, What have I got to lose? and hopped a plane to the Philippines.

“It was a big risk, absolutely. But the alternative was not so good, either,” Phillips, who is in his late 50s, says, sitting down in his office. His blue eyes are set off by lined, ruddy skin—the skin of a crabber, not a CEO. A coffee-table book rests on a table: New Guinea Ceremonies.

Phillips spent a month crabbing on Bantayan, an island that was still without electricity. In many ways, it reminded him of his native Hooper’s Island, where his parents, ignoring the criticism of their friends and neighbors, had been the first of the locals to put a bathroom in their house. On Igbon, another island, Phillips was the first American to visit since World War II, when GIs liberated the residents from Japanese occupation. The islanders held a ceremony on his behalf—grateful, he says, “to thank an American.”

The feelings of gratitude were mutual. Phillips had found what he was looking for.

“There is nothing better than fresh Maryland crabmeat,” he allows, freely conceding the criticism he will get from his own staff for such a remark. “It’s the premier crabmeat in the world—it’s a great product. The problem is, there’s just not enough of it anymore.”

The Asian swimming crab was close enough to the blue crab to satisfy him, and its population was large enough to sustain a commercial venture. Phillips also found in the Philippines a surplus of workers with an invaluable knowledge of local waters and some 7,000 islands from which to fish. Not least, he found an absence of competition: No one in Asia at that time was commercially fishing crab.

In 1990, Phillips purchased land on Bantayan on which he’d open a processing plant. He replicated the business model the company had used for decades on the Eastern Shore. New culture, different skin color, same tableau: Small fishing boats of men head out to sea to dredge the crabs from the deeps, while the women on the line set about steaming the freshly hauled delicacies and laboriously picking the lump and backfin. He even installed the same pasteurization system the company used in Baltimore.

Over the next decade, Phillips rolled out plants in Vietnam, China, India, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Ecuador. (A new plant recently opened in Mexico.) Today, 4 out of every 5 of the company’s 18,000 employees can be found in Asia. A company that once feared it would not have enough crab to sustain its operations now had more crab than it knew what—

No, it knew exactly what to do with it. Endowed with a seemingly ceaseless supply of crab, Phillips was able not only to meet demand but exceed it.

The company quickly restructured itself, reconceiving its mission. It undertook a “guerrilla-style” marketing campaign, taking out ads in industry journals, touting the “rigorous pasteurization” that ensured an 18-month shelf life and championing the fact that the meat arrived already picked. It opened up sales offices in seven cities across the country, including Chicago and Dallas, neither of which could ever be accused of being a seafood town. The growing national presence led to two significant contracts: one with Sysco, the nationwide wholesale restaurant supplier, and one with Costco, the wholesale grocery giant. Supply had created demand.

Not everything, however, went according to plan. For one thing, people noticed.

In 2002, the Bethesda-based Made in the USA Foundation filed a class-action suit on behalf of Maryland consumers, seeking a temporary restraining order against Phillips. It claimed that the labeling on the company’s packaged goods violated the Lanham Act, which prohibits false designations of origin and false descriptions of products. A district court disagreed. The foundation tried again with the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. It, too, disagreed, ruling last year that the Lanham Act is meant to protect businesses against competitors’ false advertising.

Attorney Joel Joseph, the onetime Nader’s Raider who brought the suit, argues that the courts were wrong, that the law is meant to protect consumers. He cites the act’s language: “Any person who…uses in commerce…any false designation of origin, false or misleading description of fact, or false or misleading representation of fact…shall be liable in a civil action by any person who believes that he or she is or is likely to be damaged by such act.”

Joseph still sounds angry more than a year later. “The package says that Shirley Phillips’ recipe has remained unchanged,” he says. “Well, she wasn’t making it with Asian crabs. She was making it with Maryland crabs. It’s a lie. People don’t know what they’re buying.”

Maybe not, but they’re buying. According to Restaurants & Institutions, crab cakes, the erstwhile regional, seasonal treat, are No. 7 on the list of most popular appetizers on restaurant menus across the country. And rising.

There have been holdouts along the way, of course: foodies, purists taking a stand, righteous keepers of tradition. Several restaurateurs in the area (all from local, privately owned restaurants, most off the record) say they refuse to use imported crab. But they’re in the minority.

“It’s not the same,” says Bill Edelblut, the owner of O’Donnell’s Seafood, in Gaithersburg. “Our most loyal customers, they’d notice for sure.”

But would they?

I decide to convene a blind taste test to find out. I invite four participants to Sushi-Ko, the highly regarded sushi bar in Glover Park, to render their judgments.

Three are chefs: Robert Wiedmaier, of the French-Belgian Marcel’s, in the West End; Jamie Leeds, of the recently opened Hank’s Oyster Bar, in Dupont Circle; and Koji Terrano, who mans the counter at Sushi-Ko. All three are sticklers about finding the best, freshest seafood available.

The fourth invitee is a Washington City Paper account executive, David Walker, a self-described foodie and the control for this particular experiment. With his untrained, though not unsophisticated, palate, he seems a fair stand-in for D.C.’s relatively savvy upscale diner.

The panelists are to sample five crabmeats in all. Three are of the jumbo lump variety: fresh Callinectes sapidus from North Carolina and Virginia, and Portunus pelagicus from Southeast Asia—Phillips’. There are also two of backfin crab: one fresh from Maryland and one from Phillips. Other than Phillips’, I’ve made no effort to track down a particular brand of crabmeat. The point is to set out packaged crabmeat that anyone could expect to turn up on an ordinary trip to the grocery store in mid-June.

In the kitchen, the Sushi-Ko staff divides the meats into equal portions, setting them out carefully on lacquered, green ceramic plates divided into quarters. Each quadrant contains a small amount of a different crabmeat. A small teacup placed in the center of the plate contains the fifth.

The panelists eat in silence at the sushi bar, taking notes.

After five minutes, I ask them to name their favorites.

The chefs have independently arrived at a consensus. Wiedmaier jabs a finger into the northwest quadrant of his plate, which will later be revealed to contain the North Carolina crab. “That’s the one,” he says, nodding. “That’s local crab, right there. That’s good.”

Leeds agrees, praising it for being “delicate” in texture, with a “good mouthfeel.”

Terrano, whose command of English is not always what he would like it to be, describes its flavor as being “round,” holding up his score sheet to show a circle. Above the circle he has written, “Sweet.”

We all turn our attention to Walker, sitting in the corner of the bar. “I don’t know,” he says. “I kind of liked this one.” He points at the southeast quadrant. He praises its lumps—the biggest, whitest, cleanest of the three brands. This meat will turn out to be Phillips’ imported, pasteurized lump crab.

“It’s got big pieces, but it didn’t have any flavor,” says Wiedmaier.

Leeds makes a face. “It had a chemical aftertaste to me.”

“Yeah,” says Wiedmaier, “it’s canned. It’s tinny. It’s not natural.”

Terrano holds up his score sheet. In the southeast quadrant, he’s drawn what looks to be an agitated amoeba—the kind that you see in those TV commercials for antacids, the kind that designate indigestion.

Walker is chastened.

Wiedmaier reassures him. “For most people, their psychology [with crabmeat] is the size. They get a crab cake and the first thing is, ‘Oh, look—jumbo lump.’ Well, here, it’s inferior product, but psychologically it’s the right one, right?”

Walker nods. “I may think I’m a foodie, but it was the appearance that got me, totally. I ate with my eyes.”

So the first lesson is that people will find plenty to like about Asian crabmeat.

The second is that, as poorly as the pasteurized Asian crab has performed in this test, according to the chefs it’s not beyond rescue. Add a spoonful of mustard, a couple glops of mayo, a few squeezes of lemon, and it might finally begin to taste like something.

Like something they themselves might consider eating? I ask. Something good?

“No,” Wiedmaier said. “But for most people, good enough.”

The third lesson is that the chefs’ judgments against Phillips’ product ought to be weighed alongside this consensus admission: All say that they would consider using imported crab over local or regional, so long as the quality were high enough.

On a sweltering day in early July, I drive out to Cambridge, Md., a historic coastal community that for more than a century has depended on its crab industry to maintain its modest standard of living.

Like much of the Eastern Shore, Cambridge has the look and feel of a midcentury American small town. The streets are lined with white clapboard homes, the local Dairy Queen is a community gathering place, and in the days leading up to the Fourth of July, you can find kids placing small American flags on the sides of the road.

A generation ago, crab processing was the dominant industry in town. Now there are only three plants, plus three more on nearby Hooper’s Island—including the A.E. Phillips plant, the family’s first business and one of only two plants the company still maintains in America. All are struggling to stick around.

The town of Crisfield, an hour and a half away, serves as a warning. At one time, the town was the epicenter of the crab industry on the Eastern Shore; today, many processors have sold out and gone into real estate. The Captain’s Galley, a processing plant as well as a popular restaurant as recently as early this year, is today a condominium complex. Many of those who remain in the business have transformed their operations from the processing of hard-shell crabs to the farming of soft-shells. The idea is that soft-shells, unable to be tinned or pasteurized, are beyond the purview of companies that depend on the resources of foreign shores. But this is, experts agree, merely a stay of execution. Phillips and other companies are at work developing a method to preserve these tender, highly perishable delicacies so that they can be shipped from Asia.

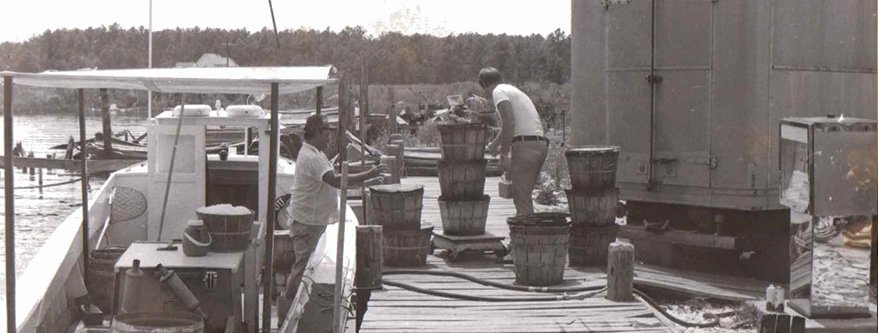

One morning I sit down with Jack Brooks in his cluttered office, outfitted with a line drawing of a Maryland clipper ship and a giant feed bag advertising his company’s crushed oyster shells. Brooks is the owner of J.M. Clayton Co., the oldest crab-processing plant in the world, opened by his great-grandfather John M. Clayton in 1890. The building sits on the banks of Cambridge Creek, yards from the Choptank River, and on this hot, humid day the air around the plant is thick with the smell of crab shells rotting in the dumpster—“talking back a bit,” as Brooks puts it. In his fireplug build and blunt, pragmatic demeanor you sense the can-do qualities that have defined the family line.

“What can I do for you?” he asks, removing his thick, tortoiseshell glasses.

I start in on my questions about the impact of importation on his business. The corners of his mouth turn downward into a deep-lined frown. No, he has not yet “gone offshore,” but he wouldn’t rule out the possibility that he may be forced to do so one day soon. Business has fallen off by 40 percent these last few years.

Brooks refuses to assign blame. He exempts both his colleagues who import crab and their wholesaler customers (“People do things for reasons that suit them best, I suppose”) from responsibility for his current predicament. He exempts Phillips, too, citing the growing influence of Venezuelan crab as a more immediate threat to his business than Southeast Asian variety. Indeed, thanks to crab dumping, whereby Venezuelan producers have been selling off their excess supply at bargain-basement prices, the wholesale price for Venezuelan crabmeat is the cheapest on the market.

In 1998, a group called the National Blue Crab Industry Association, of which Brooks was a member, petitioned the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to secure the designation “blue crab” for Callinectes sapidus. The group wanted “blue crab” to be added to the nomenclature of designated crab species and to make sure that Callinectes sapidus alone be accorded the designation. The FDA issued a proposed rule for comment but argued that the rule would not effectively solve the problem of confusion in the marketplace.

In 2000, while the proposal was still under review, the American Seafood Distributors Association, of which Phillips was a member, submitted a petition that sought a ruling designating Portunus pelagicus as “blue swimming crab,” not “swimming crab,” as the FDA had suggested. “Blue swimming crab,” as Phillips referred to its crabmeat, was already fixed in the public mind, the organization’s lawyers argued. The FDA has yet to finalize any ruling. As a result, Phillips and other producers that import foreign product remain free to market their Asian swimming crab with the psychologically invaluable descriptor “blue.”

Brooks is bitter about that, but he hasn’t lost his sense of humor. “You can market any kind of crab as blue crab,” he says. “I guess you could call a pork chop a blue crab if you wanted.”

Another of what Brooks calls “scrapes” with regulators may have been more damaging. In 2000, Brooks was among a group called the American Blue Crab Alliance, an organization of domestic crab processors that petitioned the International Trade Commission for relief in the form of tariffs from the injury the local industry had suffered as a result of large and rapid increases in crabmeat imports. In 2002, the organization rejected the petition. The commission based its decision on a “snapshot” of the state of the industry in the four-year period covering 1995 to 1999. In 1996, imports in Baltimore were less than $1 million a year, rising to $62 million by 1999. By 2002, however, the number was $123 million—and still climbing.

Asked about the ruling, Steve Phillips explains its significance to his company this way: “I wouldn’t have this business if they had gone against us.”

I find Roy Todd across town at his terrific, family-run restaurant, Ocean Odyssey. Todd opened the business in 1986 to supplement the income the family took in from his crab-processing business, Bradye P. Todd & Son. It turned out to be a prescient decision. It currently costs him $16 to produce a one-pound container of jumbo lump crab. He sells it to local suppliers for about $11. He’s losing $5 on each container that leaves his plant. Without the restaurant, says Todd, “I’d be unemployed by now.”

Ocean Odyssey makes one of the best fried crab cakes I’ve ever eaten, the outside crunchy and light, the interior spilling over with jumbo lump picked that day in the processing plant behind the restaurant. Todd is justifiably proud of his crab cake. Almost as proud as he is of his profession, a “good, honest way of life.”

“I’d rather sell my business and walk away from it,” he says, “than sell foreign product.” He sees himself as the odd man out in a town that is increasingly turning itself over to imports.

Todd tells me he debated with himself whether he should talk with me on the record before deciding, finally, that he had nothing to lose. Business is down 60 percent from three years ago, since Phillips and the others “saturated the market.”

“Shit,” he says, “you won’t find one restaurant out of 50 in this county that can guarantee they’re using 100 percent American meat.”

Todd takes me to the processing room in back, a cool, fluorescent-lighted room where women sit at long tables laboriously picking lumps of crab by hand and filling one-pound containers for shipping. He plucks a lump from the table, holding it aloft for my inspection.

“You can’t get this meat anywhere else but here, in the Bay. That color, that sweetness. A lot of people try to duplicate it, but they can’t. You’ve tasted Phillips crab, right?” His brow furrows, a grid of lines echoing and intensifying the network of etchings at his temples. “It’s washed. It’s pasteurized. They use a product on it—SAPP. It’s a preservative, a chemical. SAPP prolongs the shelf life and whitens it. And what I always say is: Anybody who buys this crab and eats it is a sap.”

Minutes later, he returns to the theme: “It’s not Maryland crab. It’s not even American crab. I never heard of a blue swimming crab until Phillips came up with it. They’re crustaceans. They may swim. They may bite. But just as snow crab and Dungeness crab and king crab are all different crabs, these crabs are different. The genus and species are different. But it’s being marketed on the shirttails of Callinectes, and the history and reputation and tradition of Callinectes. ‘Maryland-style.’ ” He spits out the euphemistic descriptor as though it were a lemon seed. “The only thing Maryland about it is the company that’s selling it.”

An hour later, as he sits down to a glass of Coke and a midday break, I ask him about the future. His future, the plant’s, the industry’s.

He sighs. A while back, a state health inspector, new to the job, came into his processing plant, making his rounds. “You know what he asks me? He asks me if I have any problem using foreign product. The state health inspector! I know he was trying to be helpful, I know he was trying to help me stay in business, but I was shocked. It was like he was there promoting imported crab.”

That was followed by a visit from an official of the Venezuelan crab industry who’d come to town to cultivate a relationship with processors like Todd.

Todd showed him the door, but not before giving him a piece of his mind. “I told him, I said, ‘You’ve got balls of steel to come in here. There was a time when I was young, I’d try to annihilate you.’ ”

But not now. It’s not just that he’s 57 and has a bad back, the product of a recent fall from the roof of his house. Combative as he is, he knows it’s ultimately a losing battle he’s waging. Venezuela is producing 200 tons of crab a day. It’s not quite as sweet and mustardy as the beloved blue crab from the Bay, but it’s relatively close. And far more cheap and plentiful, besides. Crab is going the way, in his lifetime, of the canning industry and steel mills.

He takes a long sip of his Coke. “Right now,” he says, “the American blue-crab-processing industry has one foot in the grave and one foot on a banana peel.”

Browse the frozen-food section of your local grocery store and you’ll see nearly as many Phillips boxes as Mrs. Paul’s. Crab cakes. Mini crab cakes. Crab balls. Crab soups. Shrimp-and-crab cakes. Penne pasta and crab. In all, there are 20 different products for the consumer to choose from, with more on the way. In May, Phillips rolled out its “Asian Rhythms” line of products, which includes pad thai and tom yum kung soup made with shrimp the company has begun sourcing in Thailand. Though it made its name as a restaurant business, Phillips today is, for all intents and purposes, a packaged-foods business.

The ramifications of the company’s reinvention have been profound. It has transformed no less than crab itself, in the words of Phillips President Mark Sneed, from a local “cottage industry” to a “national and even global operation.”

We are sitting at a table in the Silver Spring outlet of Phillips Famous Seafood Express, one of what was once planned as a long string of “fast-casual” counter-service restaurants the company intended to open in the next several years. Instead, Phillips has recently decided to change course, opting instead to concentrate on expanding its airport-restaurant business, in addition to the seven full-service restaurants that stretch from Baltimore to Savannah, Ga. An eighth is scheduled to open soon.

As the company’s global reach has widened, the restaurants it once banked its reputation on matter less and less. The Chesapeake Bay, once its only source, is an even smaller presence. It hardly exists for the company anymore, except to supply a limited number of whole crabs for the restaurants. And as a charity case: The Phillips family has donated more than a quarter of a million dollars to the University of Maryland’s Center of Marine Biotechnology to fund a crab-research program, an environmental initiative to resuscitate the Bay’s Callinectes population.

A new market for the company’s products has emerged: Europe. Sneed estimates that someday 40 percent to 50 percent of sales will be across the Atlantic. He shares a piece of market research: The average American eats 12 to 13 pounds of seafood a year. The average Spaniard? Sixty-five. (Later, in his office, he’ll lay out the company’s definition of market saturation in Europe: “when people start having crab for breakfast in Poland.”)

“When you look at the top 10 in the country for seafood sales, crab is not No. 1,” says Sneed. “It’s No. 7 or No. 8. So there’s still a ways to go.”

He bridles when I express skepticism at the taste of his product. “It’s because it’s been pasteurized,” he assures me. “It’s pretty close.”

I gesture at the crowd of diners lunching on crab cakes. Are they aware of the fact that their crabmeat was dredged by workers in Southeast Asia?

Sneed leans across the table. “The recipes are from here. The recipes are from Shirley Phillips and the family. We have never hidden the fact of where this crabmeat comes from.”

“But the practice of outsourcing—“

“Ninety percent of shrimp in this country are imported.…You used to be able to get tomatoes only in summertime. If you think about it, salmon used to be available only in limited supply. Does that make these things less regional? Yes. But people in Chicago want a crab cake, too. Why would we deprive them of that?

“If we don’t take advantage of the market, someone else will. It’s a global economy for everything, and that’s a good thing. Everyone wins.”

I guess the people in Chicago win. Phillips certainly wins. Do the workers in Asia win? You can’t tell me the workers here win.

You can’t tell me taste wins.

[Cited -Washington City Paper July 15–21, 2005]